Miles Wilson is a philanthropic professional with nearly 30 years of experience supporting the U.S. social sector as well as past efforts in Northern Ireland, the Netherlands, and South Africa. Miles’ work has covered a broad spectrum of core social sector activities, and he currently serves as the Deputy Director of Education Grantmaking at Ascendium Education Group. Miles was most recently a Senior Fellow with the Aspen Institute Forum for Community Solutions. This feature, Social Justice and a Relevant Philanthropic Sector, is the third in a six-part series of blog posts about his experiences in philanthropy. A version of this blog series is running on the Center for Effective Philanthropy website. Access the entire six-part series here.

During my career in philanthropy, I have worked for foundations whose grantmaking was almost entirely project support grants as well as those almost entirely general operating support grants. What I recall from those experiences was a high degree of distrust by foundations and unreasonable line-by-line reviews of budgets to determine if costs are appropriate.

As a result, nonprofits inevitably felt forced to pad their budgets in places where it would be least noticed knowing that foundation would provide the least amount of grant dollars. However, foundations would hold them to a level of performance that did not match the level of funding. I watched this scenario happen even when foundations only partially funded a project.

The foundations that provided almost entirely general operating support tended to put greater focus on initially determining alignment of missions between themselves and the nonprofits. In this case, there was a much clearer sense of partnership and trust between the foundation and nonprofit organizations.

I also saw these foundations engage with nonprofits that were funded to ensure that nonprofits had sufficient resources, both financial and non-financial, to succeed in achieving their missions. There is no doubt in my mind that the latter approach produces the greatest benefit to foundations, grantees, and the common issues and constituencies the grantee and foundations seek to impact.

The Nonprofit Finance Fund is also deeply concerned with the lack of general operating support and says, “The reality is that non-program dollars are hard to come by, which means that organizations can barely cover ordinary administration and infrastructure costs, let alone use funding to thoughtfully, strategically plan for growth or change.”

Today, logic models are broadly insisted upon by foundations large and small and cutting across nearly all types of program and initiative grantmaking. However, despite its widespread use there are real limitations and challenges with how logic models are being used.

The provision of general operating support is a powerful tool that allows nonprofit organizations to manage to their mission and do it in a manner that allows them to act flexibly as circumstances in their operating environments require. General operating support is the ultimate vote of confidence to a nonprofit. General operating support is used most effectively when the nonprofit has clear alignment with the funder and where the funder makes long-term multi-year grants to the nonprofit organization. This form of funding is by its very nature strategic and demonstrates partnership with the nonprofit as they share common broad goals and interests, and work to advance each other’s success.

Another great benefit of this type of funding is that where there are long-term multi-year general operating support grants, both funder and grantee need not spend lots of time and resources trying to determine impact in the short term, but can create a more thoughtful and meaningful process of developing both reasonable reporting and an evaluation approach that is efficient, effective, and right- sized. Instead of asking for an evaluation that responds largely to the foundation’s needs, the nonprofit organization evaluates its performance in achieving its own strategic goals over a longer term where actual impact data is more likely available and will truly matter to both the nonprofit organization, its constituents, and the foundation.

I conducted a brief experiment, albeit not terribly scientific, but compelling nonetheless. I performed a Google search using a number of variations of “benefit of project support grants” and then did the same with “general operating support grants.” I could not find one report or article professing the great value of project support grants. However, I found many articles and reports about the great value and benefit of general operating support grants. Many of these positive reports were written by the most important leading voices and institutions in the philanthropic sector.

Project support is largely outdated, generally ineffective, and most of all a dangerous approach that threatens both the organizations’ sustainability and its ability to achieve its mission. It’s time for organized philanthropy to intentionally strengthen nonprofit organizations by shifting to general operating support to strengthen nonprofits, engage in a level of relationship that demonstrates trust, partnership, and the necessary humility that every good grantmaker should have.

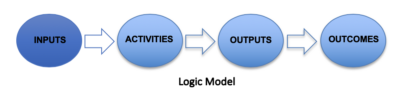

Many years ago, I recall the former chairman of Chrysler Motors, Lee Iacocca, use the phrase “form follows function.” It’s a simple phrase that makes complete sense: the form that something takes should be based on its intended purpose. It’s been nearly 30 years since I first learned about the Logic Model approach to evaluation and saw how quickly it was permeating government, nonprofit, and business organizations and programs. At first glance, the logic model appears to offer a visual and simple way to think about moving through specific envisioned steps of an effort from concept to outcome.

Today, logic models are broadly insisted upon by foundations large and small and cutting across nearly all types of program and initiative grantmaking. However, despite its widespread use there are real limitations and challenges with how logic models are being used.

One issue is that logic models are very linear and begin with “inputs” to lead to specific “outcomes.” Interestingly, this approach is not particularly logical as it asks one to use the means to show how one achieves a particular outcome, when in reality the outcome sought should drive the means – form follows function.

Logic models work best in simplicity but become rapidly confusing with greater program complexity, where there is need for flexibility and responsiveness to circumstances.

This is particularly true in organizations where grants support communities and populations where poverty, unemployment, social disenfranchisement, and other challenging issues are merely presenting issues. The more fundamental or underlying issues are often overlapping and do not lend themselves to clear linear “if-then”-type statements.